I’m always on the lookout for innovative approaches to improve student well-being and to create healthy, thriving communities – whether online or on campus. And as you know, Justin and I have examined a number of factors over the years which affect the experience of youth during their journey through adolescence. School climate has been one of them, and we’ve worked with so many schools across the nation to help them create environments marked by civility, peer respect, belongingness, and connectedness. Formally, school climate is defined as “quality and character of school life” and “based on patterns of people’s experiences of school life and reflects norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning practices, and organizational structures” [1:182]. We wrote a book on this in 2011, and it has become a key focal area for educators in the years since.

Recently, though, I’ve come across what has been called Authoritative School Climate. It is related to a traditional conception of school climate but builds on it. And I believe it can show us the next step we need to take as we refine our efforts to increase morale and promote positive attitudes and behaviors (and attendance, and academic achievement, and so much more!) among the students we care for.

Historical Observations

To begin, let’s first briefly summarize Authoritative Parenting, which planted the seed for this new line of inquiry. Way back in 1968, child development researcher Diana Baumrind articulated a theory which served as the springboard for a tremendous amount of research and practical work involving parenting styles. She believed that there were two major components of parenting: disciplinary structure (also known as control/demandingness) and emotional support (also known as warmth/responsiveness) [2]. And so she created three categories of parenting based on how those components might work together:

Authoritarian Parenting is when you are high on disciplinary structure, but low on emotional support. This is where you run a very tight ship when it comes to rules and expectations, but fail to display enough warmth and care to your kids.

Authoritative Parenting is when you are high on disciplinary structure, and high on emotional support. This is where you run a very tight ship when it comes to rules and expectations, but do so in a loving, supportive, warm environment.

Permissive Parenting is when you are low on disciplinary structure, but high on emotional support. This is where your rules are all over the place and randomly enforced, and where there aren’t clear expectations set, but where you do demonstrate a lot of warmth and care and love.

About twenty years later, Maccoby and Martin [28] offered a fourth style: Neglectful Parenting.

Neglectful Parenting is when you are low on disciplinary structure, and low on emotional support. This is where you lack clear rules and expectations, set and enforce them haphazardly, and also lack warmth, love, and support.

Baumrind’s takeaway was that Authoritative Parenting was the best parenting style, and should be aspired towards in every family [3-5]. That is, the parents should make and require abidance by the rules in the household, set high expectations for youth behavior, and exert a certain amount of control over the major choices their kids make [6]. At the same time, they should do this in a setting marked by unconditional love and support, affection, and meaningful communication.

Decades of research since have largely supported this notion [7-9]. And it has been suggested that these same principles might be applied to school climate [10-12], so Justin and I said to ourselves, “Yeah! Let’s study this!”

Application to Schools

Like the two dimensions of parenting offered by Baumrind, Authoritative School Climate uses generally the same components:

Disciplinary Structure – which has to do with students perceiving school rules as strict, but equitably applied, and;

Student Support – which has to do with students perceiving that their teachers want them to succeed, and will always treat them with respect.

Just like with parenting styles, there can be four styles of a school climate, depending on where the school falls on a continuum from low to high on Disciplinary Structure and Student Support:

Authoritarian School Climate is when you are high on disciplinary structure, but low on student support. This is where you run a very tight ship when it comes to rules and expectations, but fail to display enough warmth and support towards your students.

Authoritative School Climate is when you are high on disciplinary structure, and high on student support. This is where you run a very tight ship when it comes to rules and expectations, but do so in a loving, supportive, warm environment.

Permissive School Climate is when you are low on disciplinary structure, but high on student support. This is where your rules are all over the place and randomly enforced, and where there aren’t clear expectations set, but where you do demonstrate a lot of warmth towards students.

Neglectful School Climate is when you are low on disciplinary structure, and low on student support. This is where you lack clear rules and expectations, and set and enforce them inconsistently, and at the same time fail to demonstrate meaningful warmth and support towards your students.

Even though this subfield is relatively new, there is a growing body of research which says that schools marked by Authoritativeness (high structure, high support) have less bullying and violence [13-17], more positive relationships [18], and improved academic achievement [19, 20] and truancy and dropout rates [18, 21]. What is more, these factors contribute to increased student engagement [19, 22, 23], which is absolutely critical to youth well-being and thriving communities. I mean, if your students are more engaged at school, isn’t that going to lead to a great environment where morale is higher and where behavioral choices are better [24]? It just makes sense, and is supported by numerous studies [20, 22, 25-27].

However, online behaviors have not yet been examined in this framework. Since the vast majority of our work is at the intersection of teens and technology, I called up Justin and said, “let’s collect some data and look into this!” Our hope was that students who indicated to us that their school was high on disciplinary structure and high on student support (and therefore had an authoritative school climate) would experience less school-based bullying (supporting previous research on the topic) and less cyberbullying (extending the relevance of the theory). If so, we all could start tailoring our school climate initiatives to better reflect the tenets of authoritative school climate, and thereby make better headway in our goals as educators.

Sampling and Measures

First off, our study consisted of a nationally-representative sample of 1,500 students between the ages of 12-17 from across the United States. Apart from using our standard bullying and cyberbullying measures (refined over the last decade, email us if you need a copy), we used the following 21-item scale by Cornell, Shukla, and Konold (2016) to evaluate authoritative school climate. As you look over the measures, you can see the exact questions that students answered.

Disciplinary structure

1. The punishment for breaking school rules is the same for all students.

2. Students at this school only get punished when they deserve it.

3. Students are treated fairly regardless of their race or ethnicity.

4. Students get suspended without good reason (reverse scored).

5. The adults at this school are too strict (reverse scored).

6. The school rules are fair.

7. When students are accused of doing something wrong, they get a chance to explain it.

Student support

1. Most teachers and other adults at this school care about all students.

2. Most teachers and other adults at this school want all students to do well.

3. Most teachers and other adults at this school listen to what students have to say.

4. Most teachers and other adults at this school treat students with respect.

5. There are adults at this school I could talk with if I had a personal problem.

6. If I tell a teacher that someone is bullying me, the teacher will do something to help.

7. I am comfortable asking my teachers for help with my schoolwork.

8. There is at least one teacher or another adult at this school who really wants me to do well.

Findings

As we turn our attention to the results from our analyses, it is clear that an Authoritative School Climate makes a significant difference in inversely affecting the rates of bullying, cyberbullying, skipping school, and feeling unsafe at school.

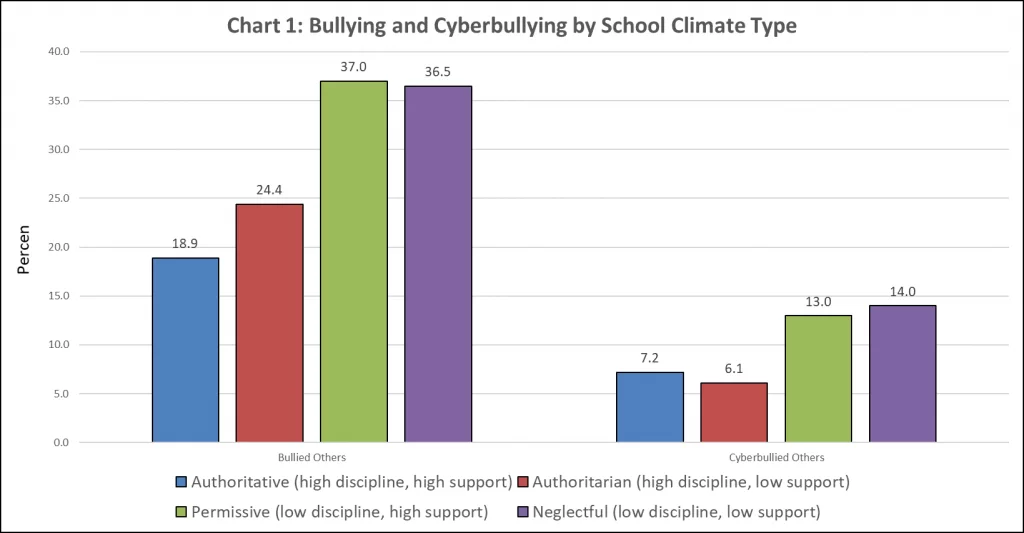

In our first chart, you can see that bullying and cyberbullying* occurs less often in authoritative schools as compared to the other three types. Said another way, in schools where disciplinary structure and student support is low, offline and online bullying is much higher.

(*To be sure, cyberbullying occurs slightly less often in an authoritarian school, but we believe this is because our numbers of kids who reported they cyberbullied someone else were a bit low. We will explore this more deeply in the future.)

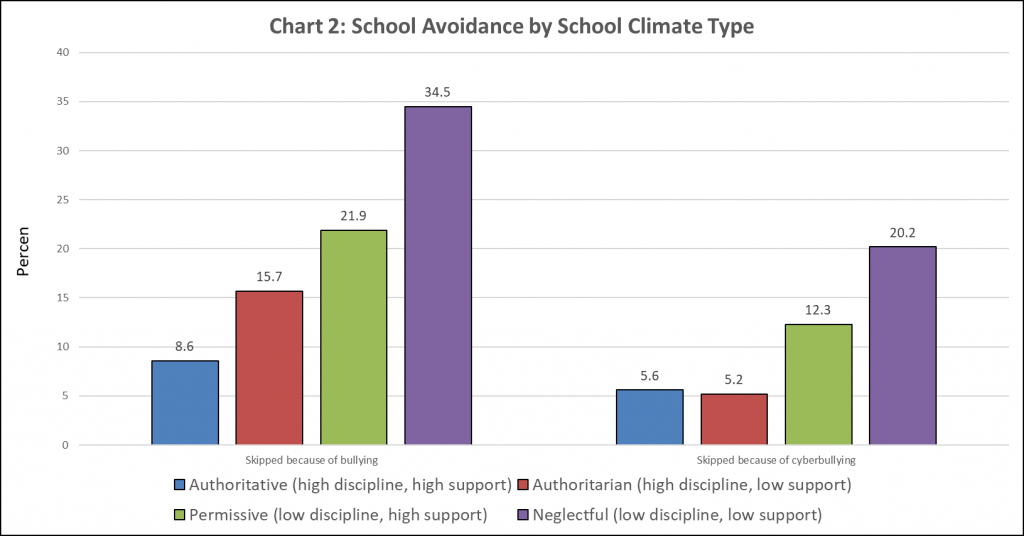

In this second chart, you can see that students are much less likely to skip school because of bullying and cyberbullying if they go to authoritative schools as compared to authoritarian, permissive, or neglectful schools.

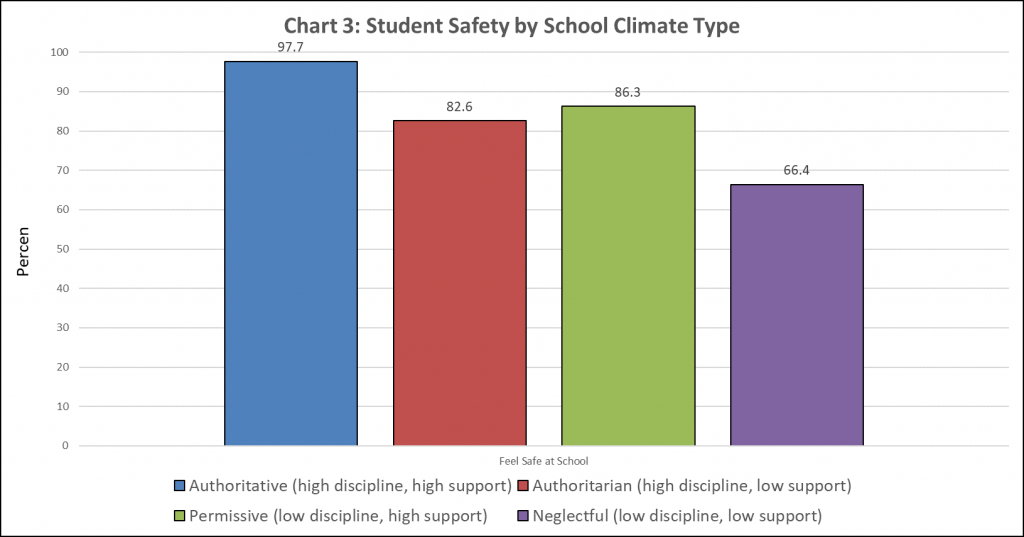

In this third and final chart, we see that students feel the most safe in authoritative schools, as compared to the other three types.

Here’s the bottom line: we should build on our general school climate initiatives by prioritizing an authoritative school climate marked by high levels of disciplinary structure and student support and warmth. When we do so, we can reduce bullying and cyberbullying while also improving attendance and feelings of school safety. And if we do, students will be more likely to come to school, connect with others, be more cognitively and emotionally engaged, and thrive.

We look forward to exploring this topic further and fleshing out how we can specifically get more schools to pursue an authoritative school climate in their policies, programming, and practices. Stay tuned and let us know if you are seeing evidence of these findings in your own school!

Suggested citation: Hinduja, S. Authoritative School Climate: The Next Step in Helping Students Thrive. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/authoritative-school-climate

Image source: https://bit.ly/2q4WZC8

———–

References

- Cohen, J., et al., School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers college record, 2009. 111(1): p. 180-213.

- Baumrind, D., Authoritarian vs. authoritative parental control. Adolescence, 1968. 3(11): p. 255.

- Baumrind, D., Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental psychology, 1971. 4(1p2): p. 1.

- Baumrind, D., Rearing competent children. 1989.

- Baumrind, D., Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition, in Family transitions, P.A. Cowan and E.M. Hetherington, Editors. 1991, Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ. p. 121-140.

- Larzelere, R.E., A.S.E. Morris, and A.W. Harrist, Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development. 2013: American Psychological Association.

- Steinberg, L., et al., Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child development, 1992. 63(5): p. 1266-1281.

- Steinberg, L., et al., Over‐time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child development, 1994. 65(3): p. 754-770.

- Hennan, M.R., et al., The influence of family regulation, connection, and psychological autonomy on six measures of adolescent functioning. Journal of Adolescent Research, 1997. 12(1): p. 34-67.

- Wentzel, K.R., Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child development, 2002. 73(1): p. 287-301.

- Walker, J.M., Looking at teacher practices through the lens of parenting style. The Journal of Experimental Education, 2008. 76(2): p. 218-240.

- Gregory, A. and R.S. Weinstein, Connection and regulation at home and in school: Predicting growth in achievement for adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 2004. 19(4): p. 405-427.

- Cornell, D. and F. Huang, Authoritative school climate and high school student risk behavior: A cross-sectional multi-level analysis of student self-reports. Journal of youth and adolescence, 2016. 45(11): p. 2246-2259.

- Cornell, D., K. Shukla, and T. Konold, Peer victimization and authoritative school climate: A multilevel approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 2015. 107(4): p. 1186.

- Konold, T., et al., Multilevel multi-informant structure of the Authoritative School Climate Survey. School Psychology Quarterly, 2014. 29(3): p. 238.

- Johnson, S.L., Improving the school environment to reduce school violence: A review of the literature. Journal of school health, 2009. 79(10): p. 451-465.

- Gregory, A., et al., Authoritative school discipline: High school practices associated with lower bullying and victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 2010. 102(2): p. 483.

- Pellerin, L.A., Applying Baumrind’s parenting typology to high schools: toward a middle-range theory of authoritative socialization. Social Science Research, 2005. 34(2): p. 283-303.

- Lee, J.-S., The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 2012. 53: p. 330-340.

- Cornell, D., K. Shukla, and T.R. Konold, Authoritative school climate and student academic engagement, grades, and aspirations in middle and high schools. AERA Open, 2016. 2(2): p. 2332858416633184.

- Jia, Y., T.R. Konold, and D. Cornell, Authoritative school climate and high school dropout rates. School Psychology Quarterly, 2016. 31(2): p. 289.

- Wang, M.-T. and J.S. Eccles, School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 2013. 28: p. 12-23.

- Gill, M.G., P. Ashton, and J. Algina, Authoritative schools: A test of a model to resolve the school effectiveness debate. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 2004. 29(4): p. 389-409.

- Appleton, J.J., S.L. Christenson, and M.J. Furlong, Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 2008. 45(5): p. 369-386.

- Rosenthal, R., How are we doing in soft psychology? American Psychologist, 1990. 45(6): p. 775.

- Henrich, C.C., K.A. Brookmeyer, and G. Shahar, Weapon violence in adolescence: Parent and school connectedness as protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2005. 37(4): p. 306-312.

- Jessor, R., et al., Adolescent problem behavior in China and the United States: A cross‐national study of psychosocial protective factors. Journal of Research on adolescence, 2003. 13(3): p. 329-360.

- McCoby, E.E. and J.A. Martin, Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. Handbook of child psychology, 1983. 4: p. 1-101.