Digital citizenship has been defined as helping youth “practice respectful and tolerant behaviors toward others” online. With the ubiquitous growth in personal device and social media use among youth – coupled with the adoption of more web-based technologies for education – many schools in the US and abroad have sought to teach digital citizenship practices to youth of all ages. This is conveyed by teachers, counselors, librarians, IT staff, and professionals at school, and hopefully is supported by similar instruction at home given the amount of time that kids outside of school are on their devices and connecting with others.

Recently, the concept has garnered an increased amount of attention as educators and other youth-serving professionals are reminded about the importance of appropriate attitudes, actions, and interactions online with so many students doing distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, Justin and I dove into our sample of 2,500 US middle and high school students (12 to 17 years old) from last year to assess these behaviors based on 12 items we came up with. Still, it can help us understand the prevalence of some digital citizenship-related behaviors among youth in recent times and can serve as a reference point for any studies that come out in the near future with COVID-19 data.

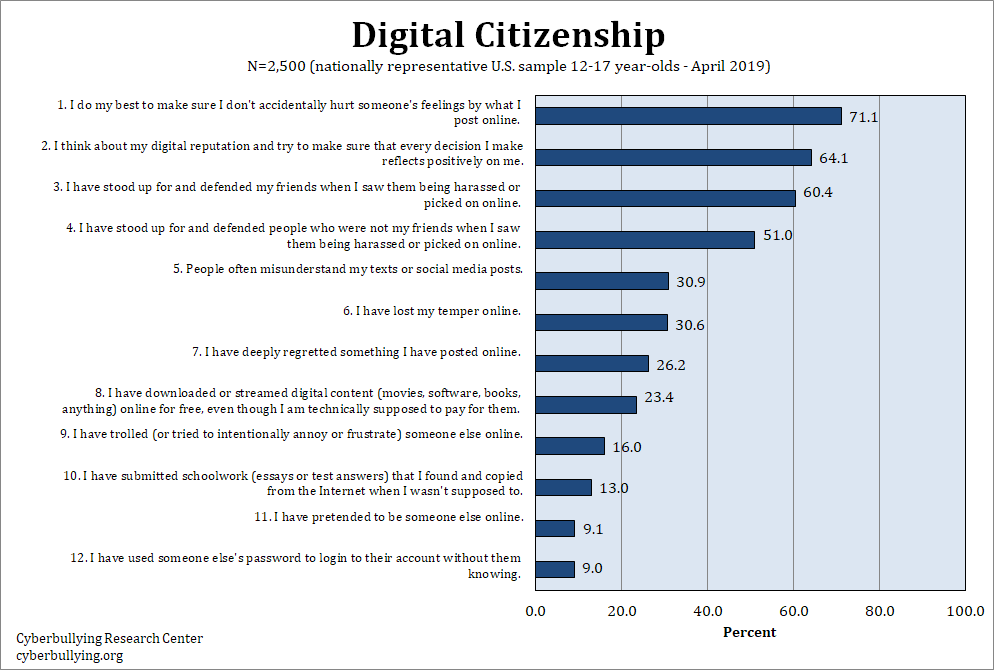

Our original response set for each item allowed respondents to choose Never, Once, A few times, or Many Times, but we’ve collapsed the last three to portray those who have – and those who haven’t – engaged in each behavior in the previous year. Please see below for a breakdown of the raw percentages:

Let’s talk through the main takeaways.

Most youth are making ethical choices online, as less than a quarter admit to pirating content illegally, only 13% admitted to copying and submitting essays or test answers (a form of plagiarism), 30.6% have lost their temper, 16% have trolled someone else, and less than 1 out of 10 (9.1%) have impersonated someone online. When we focus on teaching digital citizenship, sometimes well-meaning adults convey that the vast majority of kids are doing the wrong things on social media and the Internet, but our data suggests that is absolutely not true. We need continually (and emphatically) to highlight that most, in fact, are doing the right thing – and we want the rest of students to come on board and do the same!

When we focus on teaching digital citizenship, sometimes well-meaning adults convey that the vast majority of kids are doing the wrong things on social media and the Internet, but our data suggests that is absolutely not true.

It also seems that our kids do think meaningfully about their (and their peers’) online actions and are not unaware of the implications. Almost 3/4ths (71.1% of youth) do their best to make sure they don’t accidentally hurt someone’s feelings by what they post online, and almost 2/3rds (64.1%) think about their digital reputation and try to make sure that every decision they make reflects positively on them. Relatedly, the majority have stood up for not only their friends who were harassed or picked on online (60.4%) but also for individuals who were not their friends (51%). That’s awesome. I love to see that. I wish I had some comparison numbers from past years to see if these percentages are trending up, but this is the first year we asked these questions.

I would like to believe that regular conversations with students over recent years about being upstanders instead of bystanders are actually making a difference.

I would like to believe that regular conversations with students over recent years about being upstanders instead of bystanders are actually making a difference. I also hope that this conveys a student population that cares about injustice and wants to put a stop to it when they see it, regardless of who is being targeted. To be sure, it would be amazing if the numbers indicated more students were doing the right thing online, but they do give me a lot of hope. Some students are making wise decisions, demonstrating empathy, and being respectful instead of rude. Some are speaking up and intervening, instead of just staying silent and minding their own business.

These numbers are encouraging. But recently I realized that they are also incomplete.

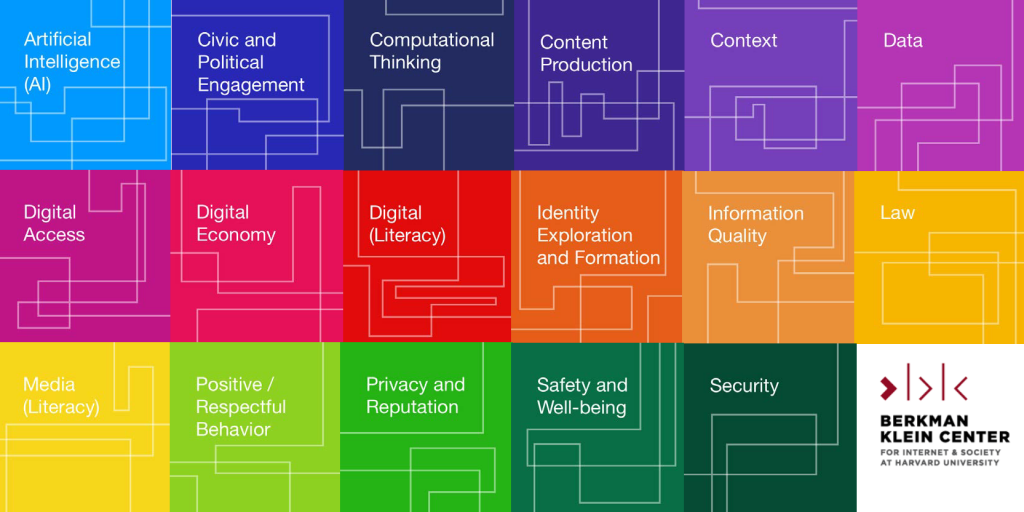

About a week ago, some of my colleagues from Harvard – Sandra Cortesi, Alexa Haase, Andres Lombana-Bermudez, Sonia Kim, and Urs Gasser – released a new 93-page thought piece on what they have termed “Digital Citizenship+” (plus) – which they define as “the skills needed for youth to fully participate academically, socially, ethically, politically, and economically in our rapidly evolving digital world.” In their deep dive, they mapped a set of 35 frameworks that have previously tackled digital citizenship or related concepts (like Internet safety or media literacy) and then discuss how these can be grouped into 17 areas to make up their new conceptualization: artificial intelligence, civic and political engagement, computational thinking, content production, context, data, digital access, digital economy, digital literacy, identify exploration and formation, information quality, laws, media literacy, positive and respectful behavior, privacy and reputation, safety and well-being, and security.

Digital Citizenship+ is defined as “the skills needed for youth to fully participate academically, socially, ethically, politically, and economically in our rapidly evolving digital world.”

From my experience, most professionals disproportionately focus on only a few. The ones that stick out to me – and seem to comprise the basis of what I see in schools around the nation – involve Positive/Respectful Behavior (being kind, empathetic and responsible), Safety and Well-being (keeping at bay various forms of victimization), Privacy and Reputation (digital footprints, etc.) and Security (passwords, personal information, etc.).

Since Justin and I work to prevent cyberbullying, sexting, digital dating abuse, sextortion, and related forms of wrongdoing online, we also focused narrowly on certain elements when attempting to measure digital citizenship behaviors (or, in many cases, examples of a lack of digital citizenship). In the Chart above, you can see that: the area of Law is partially measured by our items 8, 10, and 12; the area of Privacy and Reputation is partially measured by our item 2, Civic and Political Engagement are partially measured by our items 3 and 4; and the lion’s share of our items (1, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 11) partially measure Positive/Respectful Behavior.

It is arguable that focusing only on the development of these skills will not do enough to prepare our students to succeed in a much broader digital landscape. They will help, but they are not enough. We used to say that “content is king” but now it’s accurate to also say that “data” and “information” are equally as important. As such, we do a disservice to our students if we focus only on the aforementioned, limited components of digital citizenship and neglect the following others:

Artificial Intelligence: having a general understanding of how this works, and the issues of bias and ethics surrounding the creation of algorithms. It can’t just be a buzzword we throw around. Shouldn’t all of our students be able to talk in general terms about this?

Civic and Political Engagement: being able to participate in social justice causes and other matters that affect communities, particularly ones that do not receive as much attention. We tell our students to “be the change” – but are we equipping them to actually do so using the most powerful tool ever created (the Internet)?

Computational Thinking: obtaining a basic understanding of how terms involved in computation can positively affect all of the work we do (“iterating,” “looping,” etc.).

Content Production: it seems like many of our students are learning skills like video-editing, digital photography, live-streaming, podcasting, and blogging on their own. That’s wonderful, but they could use some more guidance on how to do this as well as possible, thereby saving them time and frustration in making mistakes that could have been prevented with some education from those who have gone before.

Context: Being intentionally aware of contextual factors that matter – perhaps race, sexual orientation, religion, location, political leaning, etc. Are our youth growing in the ability to identify sensitive issues or other relevant aspects in their online interactions, or are they generally just focused on themselves?

Data: Our students should have some kind of skillset in working with data – creating it, collecting it, analyzing it, and evaluating it. Data is everything these days and developing an expertise in data science and analytics will likely increase one’s employment potential in the future. At the very least, some familiarity is necessary.

Digital Access: Being able to access the Internet and all related tools. This is a human right, in my opinion.

Digital Economy: Understanding how economic, social, and cultural capital can be extracted and earned from online/offline interactions. We know about the gig economy, but I am a person who believes that the Internet will be so much more inextricably intertwined with our lives and ability to make a living not just in the next twenty years, but in the next five.

Digital Literacy: Being able to use all that the Internet has to offer to create, share, and connect/interact. We cannot assume that kids are naturally going to develop this skill simply by spending time online. To become fully literate, they need to be specifically educated on so many tools, resources, repositories, and apps that they’d never naturally stumble across.

Identity Exploration and Formation: Rather than simply happening organically and without guidance, we want our youth to understand how they can use digital tools to explore their own identity.

Information Quality: Using the Internet to access and benefit from the information it has to offer. Do you know where to go for the most reliable information related to health and exercise? What about the upcoming election? What about religious beliefs? What about investing? We need to help our students understand what is quality information, and what is not.

Law: Understanding various important laws associated with the Internet (e.g., copyright infringement, privacy invasions, defamation, unauthorized recordings, harassment, etc.) and applying them to guide and constrain one’s own behavior. Ignorance is no excuse for not complying with the laws we have in place, and we want students to respect the rights of others, and in turn have their own rights respected.

Media Literacy: Being able to create, circulate, evaluate, and analyze content in any media type, form, community, or network. This is obviously a key skill which we’d hope that every student develops during their schooling because they’ll likely be doing this in some fashion throughout their life, regardless of their work.

That’s 17 areas in total. You can learn more about each here – and also access a compendium of over 100 educational tools to help you provide instruction and guidance in each of these areas in classrooms, households, and community organizations. Educators, check them out and put them into practice when the new school year begins! Do this not because of any possible mandate or directive from your supervisor, but because it matters so much for our increasingly connected students!

To be sure, this list may not be complete. My friend Anne Collier has recently suggested that three other areas are missing – explicit reference to social and emotional learning (SEL), the historical context (the history of the Internet!), and rights (what participatory rights do Internet users have?). I agree that each of these merit further examination and inclusion. We need our youth to develop their SEL skills to become the best versions of themselves regardless of where they interact. And if we neglect teaching (and learning from) the history of the Internet, we may be doomed to make avoidable mistakes. Finally, youth especially have had some of their digital rights curtailed because of fear and moral panics, and this must be addressed to best empower them to make a positive difference in their spheres of influence.

If we neglect teaching (and learning from) the history of the Internet, we may be doomed to make avoidable mistakes.

Future research endeavors would do well to create specific measures and scales to approximate competency in each of these areas. To be sure, this is the hard part – and scholars will likely stumble a bit as they figure out the best ways to measure these skills and behaviors. However, just like we (the entire field) have made solid progress when it comes to measuring cyberbullying, sexting, and digital dating abuse, we’ll eventually get there when it comes to measuring, studying, and evaluating the value of Digital Citizenship+ individually and collectively. That will greatly help inform our educational efforts in the trenches to best meet the needs of current-day youth on their way to becoming adults who can positively contribute to our digital-based economy, society, and community.

Suggested citation: Hinduja, S. (2020). Digital Citizenship in 2020 and Beyond. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/digital-citizenship-research

Facebook Research provided support to collect the data presented in this post.

Image sources: @ballalatmar (https://bit.ly/2M4G6T2), Gene Walsh, Digital First Media (https://bit.ly/2X9Ztk3)