As someone who teaches criminal justice in a university setting to many future law enforcement officers, I was appalled by the treatment of George Floyd by members of the Minneapolis Police Department. Appalled, but not surprised. Regrettably, these incidents continue to happen at an alarming rate and the last month of worldwide protests have been a clarion call for meaningful change. Reform is unquestionably required, but what about the proposal to substantially reduce or altogether eliminate the police? And while many are rightfully focused on the implications of these ideas on violent crime, another question is how a reduction in police services will affect cyberbullying and other adolescent school and online behaviors.

Defund the Police: Rhetoric or Reality?

As a result of recent events some have begun to reimagine what public safety should look like. As a slogan, “defund the police” is sensational and prescriptive. For most people though, “defund the police” doesn’t literally mean defund the police. If I understand the sentiment behind the placards, most are arguing for systematic reforms and resource reallocation that would shift money from the “crime fighting” activities of police officers to the community development activities of social workers and counselors.

It is true that we’ve asked a lot of police officers. They are often the first people we call when something bad has happened, whether they are capable of resolving the situation or not. Your typical police officer is well-versed in how to enforce the law (e.g., make an arrest or investigate a crime), but most circumstances they encounter will not require this skillset. More often, they are summoned to solve a social problem or assist in a medical emergency. One idea floated is to remove these service aspects of their job, and give them to someone better equipped to respond.

Your typical police officer is well-versed in how to enforce the law (e.g., make an arrest or investigate a crime), but most circumstances they encounter will not require this skillset.

These are not novel suggestions. State and local governments have long grappled with how to best distribute increasingly scarce funds to further public safety. An example of this is something referred to as justice reinvestment. The idea behind justice reinvestment is you move resources away from law enforcement (most notably jails and prisons) and into social assistance programs like mental health services, substance abuse treatment, and other crime prevention strategies. The goal is to invest in avoidance rather than after-the-fact accountability. You could spend money to put more police officers on the street or to build a new prison, or you could direct resources into initiatives designed to prevent people from getting into trouble in the first place. For example, does it make sense to pay $35,000 per year to house an inmate in a state prison for a drug offense when we could instead pay about $100 per person to implement a proven substance abuse prevention program?

Justice reinvestment is a data-driven policy. Proponents advocate for a problem-solving approach that identifies underlying causes of deviant or disruptive behavior (drug addiction, homelessness, mental health problems) and seek to invest in ways to address those. Most of these people are not anti-police provocateurs, but concerned citizens looking to make their communities safer.

The Role of School-Based Law Enforcement

Along with the national call to reduce funding for the police, some school districts are severing agreements with local police departments to staff officers at schools. Is this just another knee-jerk reaction to frustrations with the police or a justifiable response to unrealized expectations about improved school safety?

School Resource Officers (SROs) (also sometimes referred to as School Liaison Officers) began appearing in schools in the 1950’s but burgeoned amid a glut of federal funding for more local cops following the Columbine High School shooting in 1999. SROs are sworn police officers with full arrest powers who are employed by a police department (with costs often shared with the school district). There is no good data on the current number of SROs serving in U.S. schools, but the National Association of School Resource Officers estimates the number to be somewhere between 14,000 and 20,000 officers assigned to about 20% of K-12 schools.

There have been several high-profile examples of school-based police officers using excessive force when interacting with students, and there is no question that incidents that would have previously been handled by educators and parents are now more often being treated as crimes (such as a water balloon fight at a North Carolina high school).

It’s also true that research on the value of SROs is mixed at best. Studies show that students don’t feel any safer at school when an SRO is present. In addition, schools with SROs have a higher rate of suspensions and expulsions. Moreover, having police officers in schools leads to more student arrests for particular offenses, especially disorderly conduct, and officers assigned to disadvantaged schools tend to enforce the law more strictly. It is difficult to know from this research, however, whether the addition of an officer resulted in more disciplinary problems and extreme responses, or if severe problematic behaviors led to the addition of the officer.

It is also evident, however, that officers who are better trained and more thoughtfully integrated into the school culture are more effective at supporting students in crisis. Some research has also found that with more SRO-student interactions comes more positive attitudes. In short, it seems to really matter how well SROs are trained, how motivated they are to connect with kids, and whether they have the autonomy and support from their police department and school needed to build positive relationships on campus.

New Research on Law Enforcement’s Role in Cyberbullying Education and Response

Coincidentally, I recently published a new paper with two friends who routinely study police practices. The data analyzed in this paper come from a decade-long project where we surveyed law enforcement officers (mostly from the United States, but a handful were from other countries) about their perceptions of—and experiences with—cyberbullying and sexting. In 2010 we surveyed about 1,000 officers (one-third were SROs while the others were traditional officers). We learned back then that most officers didn’t know much about cyberbullying and few (17%) had directly investigated cyberbullying cases. Moreover, SROs were significantly more likely than traditional officers to believe that law enforcement can play a significant role in addressing cyberbullying.

Officers who had personally handled a cyberbullying case previously, or who had worked in a school in the past, were more likely to see a significant law enforcement role in dealing with cyberbullying than those who hadn’t.

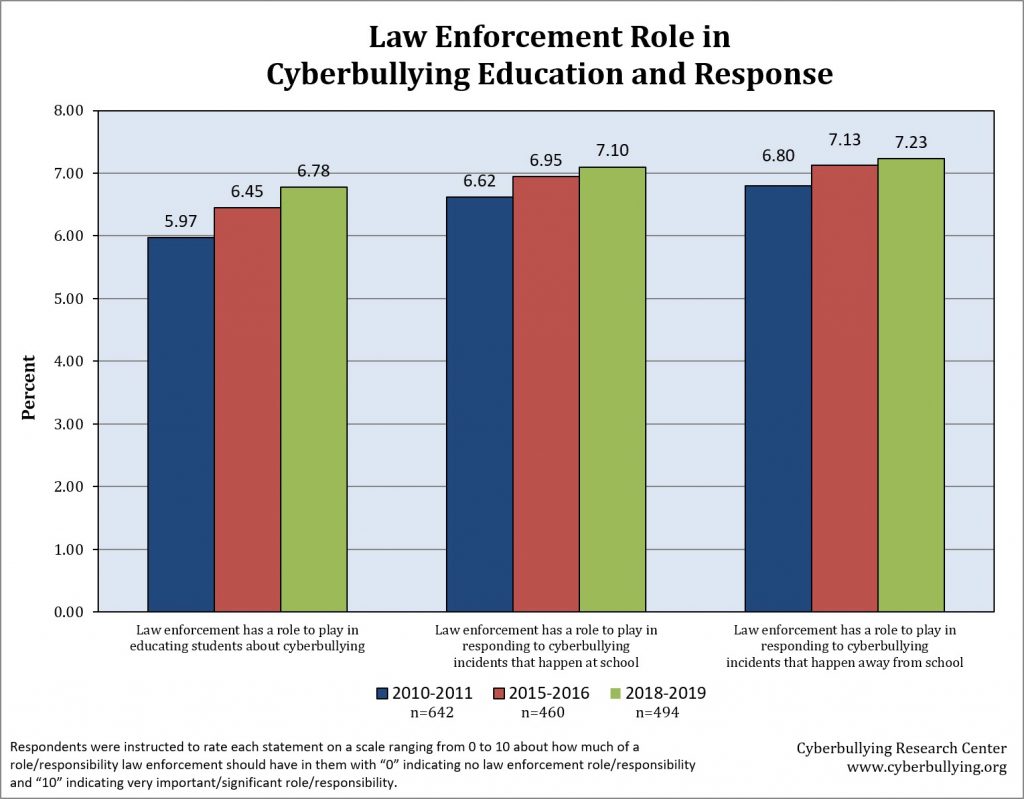

We have continued to regularly survey traditional officers, and in our latest paper found that a still small, but increasing, number of officers had investigated a cyberbullying case (up to 26% in 2019). We also found that, over time, officers increased their ratings of the extent to which law enforcement should be involved in educating about, and responding to, cyberbullying incidents. And as we suspected, officers who had personally handled a cyberbullying case previously, or who had worked in a school in the past, were more likely to see a significant law enforcement role in dealing with cyberbullying than those who hadn’t.

Conclusion: Allocate More Resources for Recruitment and Training

I personally believe that the vast majority of law enforcement officers are good, decent, well-intentioned, and not racist. There definitely are bad actors, bad supervisors, and systemic problems in some departments. These need to be rooted out – whether the officers are in schools or on the streets. Thoughtless removal of funding will not solve these deep-seated problems and may actually serve to exacerbate them. Recruitment, retention, and thorough training of good officers is expensive and blindly pulling resources without consideration of the consequences is dangerous. Most of the officers I know—many of them former students—would welcome additional training and support to do their jobs more safely and effectively.

Our research shows that officers assigned to schools who have experience dealing with cyberbullying cases are more willing to get involved to help resolve the situation. That doesn’t usually mean issuing a citation or making an arrest. Rarely do police officers need to invoke their formal law enforcement role when dealing with cyberbullying or other incidents involving students at school or online. But they understand the negative impact of these behaviors on the wellbeing of students and know it is necessary to assist.

A law and order or “warrior” mentality will not work in a school setting. It will create fear and turn students and staff against the officer who will be viewed as an occupying force, not a servant to assist in solving problems. The much-heralded community policing approach does hold some promise, however. A well-trained and intentionally recruited SRO would be available on the rare occasion that a serious incident requiring law enforcement occurred, but would also be present day in and day out on campus to develop positive relationships with students and assist in various educational and support efforts. Officers with an educator/counselor mindset could contribute meaningfully to a positive school climate and school safety.

I often think about a comment an SRO made to me back in 2010 when we were talking about cyberbullying: “We need more training to deal with these pain-in-the-ass cases!” This sentiment illustrates so much. This officer was acknowledging the challenges in handling cyberbullying incidents and was desperate for help. He didn’t feel he had the tools to manage them. While he was probably most concerned about policies and procedures, he also likely lacked conflict resolution and de-escalation strategies that work with youth, along with information on adolescent mental health and special needs populations. It is doubtful that he knew much about the benefits of social and emotional learning or how to support students in a way that cultivates resilience. We need to make sure school-based officers are well-equipped to work with adolescents, and I’m not referring to the items hanging off their duty belts.

Suggested citation: Patchin, J. W. (2020). Defund the Police? Implications for Cyberbullying Prevention. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/defund-the-police-cyberbullying

Photo credit: Flickr (northcharleston)

Justin, just curious….You are mentioning about the students not feeling any safer with SROs, what about the educators? What about the parents? are the a big part of you school “atmosphere”?

Hi Jean-Yves,

This is a great question. I am not aware of any research that has examined perceived safety among staff at schools with SROs. Certainly a topic worthy of research!