The current global pandemic has greatly constrained the way people are able to interact with each other. Schools in the U.S. moved to online learning mid-March and health safety guidelines continue to warn against gathering in groups outside of immediate households. As such, teens haven’t been able to hang out with their friends in hallways, homes, or neighborhood haunts for many months. Text and video chats are great but can’t make up for the physical interaction and connection that most youth crave. That is especially true when it comes to romantic relationships.

A teacher friend of mine recently relayed a story about one of his high school students who had figured out a way to meet up with his significant other despite the stay-at-home mandate. During their weekly trip to school to pick up and drop off homework, they would sneak away and hide out in one or the other’s vehicle for a brief clandestine “study session” before returning home. This worked for several weeks until a teacher finally noticed the pattern of the two always arriving and leaving together. Kids are nothing if not resourceful.

While I cannot comment definitively on whether sexting among teens has increased over the last few months, I can say that it does seem to have increased over the last few years.

Absent the ability to connect in person, youth might turn to technology to achieve some level of intimacy. Anecdotally, there is some speculation that sexting (the sharing of explicit images) has increased during the pandemic as teens seek to satisfy their sexual desires from a distance. While I cannot comment definitively on whether sexting among teens has increased over the last few months, I can say that it does seem to have increased over the last few years. In both 2016 and 2019 we collected data from middle and high school students from across the U.S. about a number of online behaviors. One of those was sexting.

Sexting Behaviors Increasing

In our student surveys, we define sexting as: “when someone takes a naked or semi-naked (explicit) picture or video of themselves, usually using their phone, and sends it to someone else.” While some include salacious text messages in their definitions of sexting, we focus exclusively on images. We published a paper last year with a detailed look at our 2016 sexting data. Of note, only about 12% of the students we surveyed said they had ever sent a sex while 19% said they had received a sext from someone else. Boys and older students were more likely to have sent and received sexts.

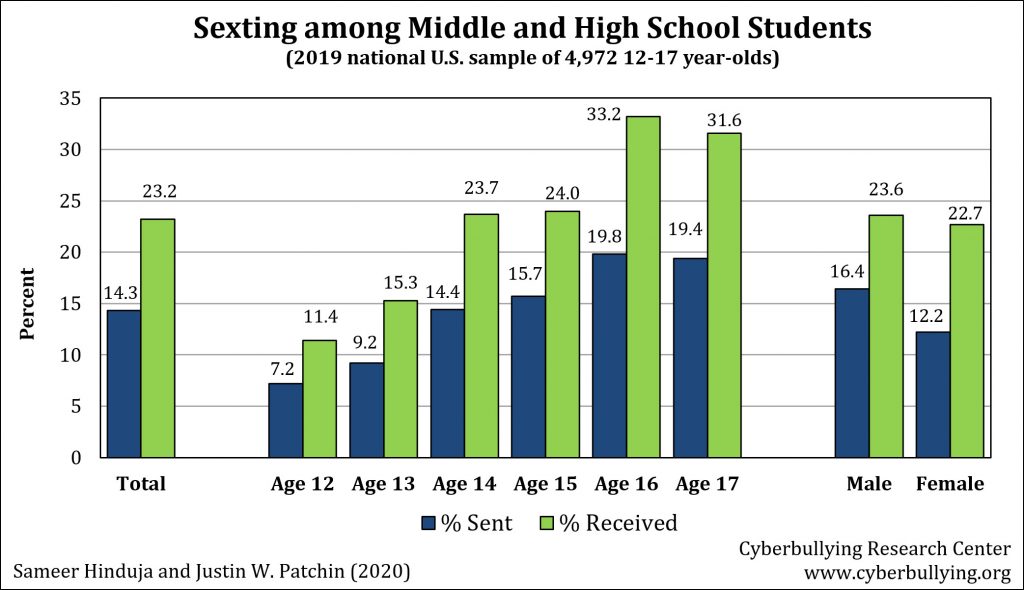

We asked these same questions among our student sample in 2019. Generally speaking we found comparable results. Relatively few students were exchanging sexually explicit images (14.3% sent; 23.2% received), with older students and boys more likely to participate. Among 15-17 year-olds in our sample, 18.3% had sent a sext (compared to 10.3% of 12-14 year-olds). A just-released report from the United Kingdom also using data from 2019 showed similar findings on that side of the Atlantic. Seventeen percent of the 15-17 year-olds reported that they had sent a nude image to others.

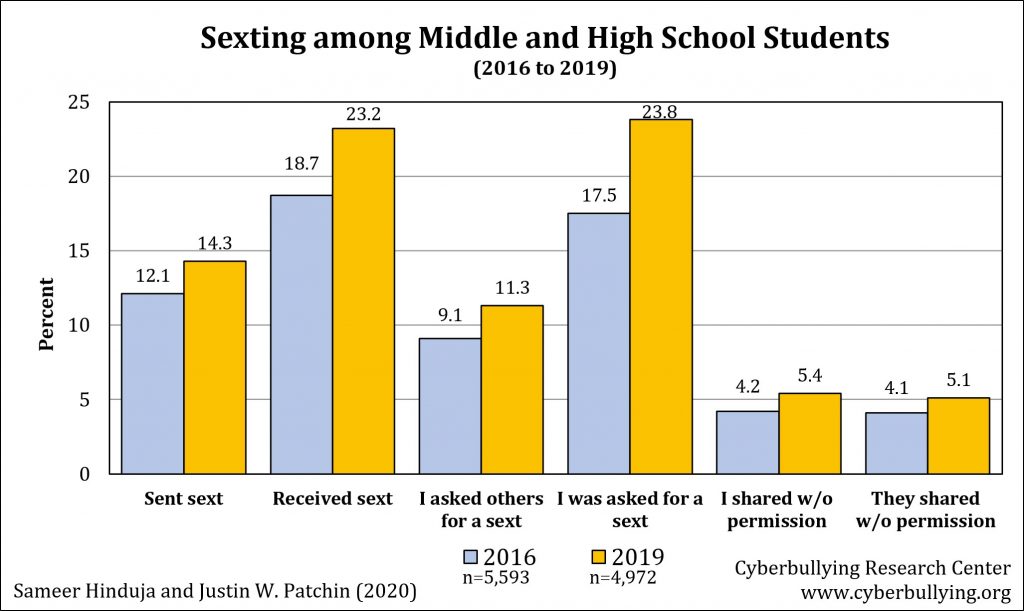

When comparing more directly our 2016 and 2019 data, we found that all sexting behaviors had increased during that period (though not dramatically). Not only had more students sent and received sexts, but more had asked others for sexts, been asked for sexts, and shared sexts without permission (see chart below).

The largest increase seems to have been in the extent to which young people are being asked to share sexts (from 17.5% in 2016 to 23.8% in 2019). That means nearly one in four middle and high school students has been asked by someone to send them a sexually explicit image. Again, overall these numbers are still relatively low, but the fact that they are increasing is cause for concern.

Another, potentially worse problem that showed an increase, is the unauthorized sharing of explicit images. The percentage of youth who said they shared an image with someone else, without the permission of the original sender, increased from 4.2% in 2016 to 5.4% in 2019. Similarly, those who believed an image they had sent to another was shared with someone else without their permission increased from 4.1% to 5.1% over that time. Private images that are shared beyond their original target is one of the worst outcomes of sexting, with potentially significant and irreversible emotional and reputational ramifications.

Let’s Talk About Sexting, Baby

It is critical that parents talk to their children about sexting. It’s not easy, but what about parenting is? Their natural desire to be intimate with others isn’t going to go away with physical separation. In fact, it is probably more likely these impulses will only become more intense with distance. Without guidance they may be inclined to satiate their urges in ways that may create significant problems later on. Teens aren’t wired to carefully consider the long-term consequences of their actions, so the adults in their life need to regularly remind them of what could happen if they aren’t careful.

Teens need to realize that once they send an image to another person, they have lost complete control over who might see it and where it might end up. Sure, most adolescents think they can trust their partner not to share the picture with others, but you never can be fully certain that they won’t. Our research shows that at least 5% of the time images are shared beyond their original target. Ask your child how they would feel if a nude or nearly nude image they sent ended up being shared with others (or worse, posted online).

Teens aren’t wired to carefully consider the long-term consequences of their actions, so the adults in their life need to regularly remind them of what could happen if they aren’t careful.

Some states are finally beginning to realize that child pornography statutes are not the best way to handle the vast majority of teen sexting behaviors (see all state sexting laws here). For predators who groom, manipulate, and pressure a child to send explicit images, implicating the formal law may be necessary. But most teen sexting involves the willing exchange of images with a romantic partner. We nevertheless probably don’t want teens to be doing this, but threatening to arrest and charge them as child pornographers has proven futile.

Results from our research do not match the rhetoric in some media articles that teen sexting is a widespread out-of-control problem. Messages like that actually serve to encourage more than discourage the behavior. If teens think that sexting is more common than it actually is, they may be more inclined to participate themselves: “Everyone is doing it!” The truth is that most teens are not doing it. Stressing this reality can help empower teens to say no when asked for a sext, and might make it less likely that someone would ask for one in the first place.

In “It is Time to Teach Safe Sexting,” published earlier this year in the Journal of Adolescent Health, we propose a harm reduction model of sexting education which acknowledges that some youth will participate in the behavior and we should therefore offer suggestions for minimizing the worst of the possible consequences that could result. They could send flirty or suggestive photos, for example, instead of explicit ones. They should avoid sending any images that could be connected to them directly (by obscuring their face or other identifiable features). Like sex, sexting will never be 100% “safe,” but with education the hope is that fewer youth will participate and those who do will take measures to minimize the likelihood of serious fallout.

The bottom line is that whatever we are doing to deter teens from participating in sexting clearly isn’t working. Just like trying to prevent them from being with each other during a pandemic, they will find a way. Something more thoughtful needs to be considered. A comprehensive evidence-based sex education curriculum has demonstrated success at reducing teen sex and pregnancy. Perhaps it is time to consider a similar strategy if we would like to stem the rising tide of teen sexting.

Suggested citation: Patchin, J. W. (2020). Current Efforts to Curtail Teen Sexting Not Working. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/teen-sexting-research-2016-2019

Facebook Research provided support to collect some of the data presented in this post.

Image: Tim Mossholder (unsplash)