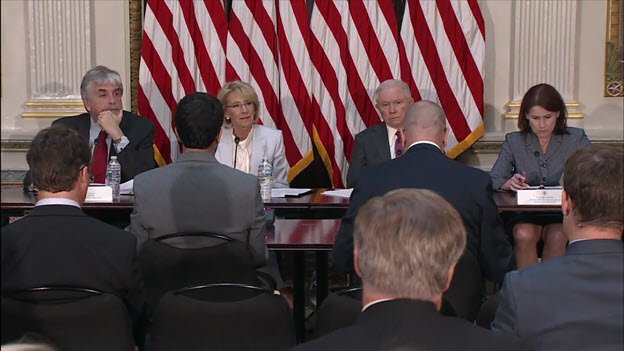

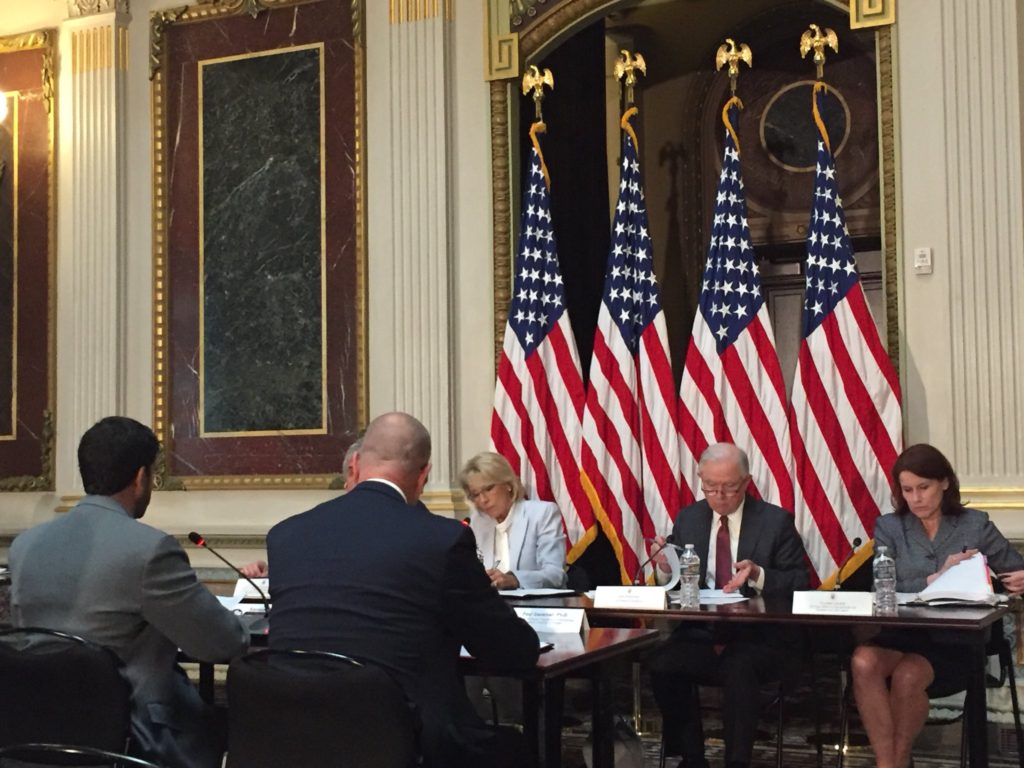

Yesterday, I testified on “cyberbullying and social media” in front of the Federal Commission of School Safety, chaired by Secretary Betsy DeVos and comprised of Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen (Homeland Security), Secretary Alex Azar (Health and Human Services), and Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Collectively, they are trying to garner insight on the ecology of schools and how we can foster “a culture of human flourishing and developing character.” I appreciated the opportunity to represent the Cyberbullying Research Center and share the research Justin and I have conducted in an effort to inform federal policy and programming in this area. They wanted specific guidance for schools, and that’s what I tried to provide them. I feel like everything went great. Plus, I love visiting Washington, DC – the remarkable history of our great nation fills my heart with pride.

Below, I wanted to share my written remarks to the Committee. It summarizes what Justin and I believe are the key focal areas to which the government should devote attention, energy, and resources. You can also watch the archived live-stream here to hear my comments and answers to their questions.

Good afternoon to each of you. I am a Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Florida Atlantic University and I also Co-Direct the Cyberbullying Research Center. Along with my colleague Dr. Justin Patchin from the University of Wisconsin Eau-Claire, I have worked to promote the positive use of technology among students through research and outreach for the last 15 years. Topics we explore in our work include a number of behaviors that mainly occur on social media. These include sexting, sextortion, digital dating abuse, digital self-harm, digital reputation issues, and cyberbullying – which I will focus on today. While I am proud of the papers and books we have published, I am most thankful for my time in the trenches working with tens of thousands of students, educators, mental health professionals, law enforcement, and parents each year on these topics. So many are in need of research-informed guidance, and I know that is why we are here.

The Prevalence and Impact of Cyberbullying

In our most recent study of a nationally-representative sample of approximately 5,700 middle and high schoolers in the U.S., 34% said they had been cyberbullied during their lifetime. In addition, 12% revealed they had cyberbullied others during their lifetime. So, that’s one-third of youth across America indicating they’ve been bullied online, and one out of ten stating that they’ve bullied others online. We also know that more than 80% of students who are being cyberbullied are also being bullied at school, indicating a strong overlap among these behaviors.

Research has tied experience with bullying and cyberbullying to low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, family problems, academic difficulties, delinquency, school violence, and suicidal thoughts and attempts. Most important to me is how negative experiences online unnecessarily compromise the healthy flourishing of our youth at school – where they spend over 6.5 hours each day. According to our research, over 60% of the students who experienced cyberbullying stated that it deeply affected their ability to learn and feel safe at school. Furthermore, 10% of students we surveyed said they skipped school at least once in the previous year because of cyberbullying. That cannot be happening.

Recommendations

Even though states work hard to get meaningful guidance to each school district, schools across each state are often left to figure out from trial and error what sort of strategies they should put into place to address cyberbullying. We go into schools all the time, and many administrators and counselors simply are not sure what they should be doing.

In terms of programming, they are trying a variety of strategies – from random assembly speakers, to random documentaries and videos, to random curricula they hear about, to random programs that capitalize on a quick emotional reaction. However, these don’t seem to effect meaningful change that lasts for more than a few weeks among the student body. At best, these approaches are inefficient, and at worst they are doing more damage than good (as kids will tune out, believe we are oblivious, and feel that nothing is going to get better). Now more than ever, our efforts must be relevant, research-based, systemic, and comprehensive instead of ad-hoc and off-the-cuff.

Allow me to share a few key recommendations. Please note that none of these are app-specific or cyber-specific because cyberbullying is not so much a technological problem (as some would like to believe). It is more of a social problem manifesting where we all increasingly live our lives: online.

1. School climate efforts

Positive school climates are marked by shared feelings of connectedness, belongingness, emotional warmth, peer respect, morale, safety, and school spirit. In one of our recent studies, we found that in schools where students perceived a better or more positive school climate, there was significantly less cyberbullying (as well as less school bullying, violence, and other problem behaviors). This makes sense because most cyberbullying among youth occurs between individuals who know each other at school – not between strangers who only connect online. Specific school programming towards this end can help reduce the frequency of cyberbullying, as well as contribute to increased student attendance and participation, higher student achievement, and less disciplinary issues.

2. Social Norming

Social norming has to do with modifying the environment or culture within a school, so that appropriate behaviors are not only encouraged, but widely perceived to be the norm. That is, schools must work to create a setting in which the responsible use of social media is just “what we do around here” and just “how it is among our students.” This can occur by strategically highlighting the majority of youth who do use social media in positive, constructive ways. If I told you that 12% of kids cyberbully others, you wouldn’t focus on spreading that fact around your student body. Rather, you would reframe and reconceptualize that statistic, and then create cool and relevant messaging strategies emphasizing that the vast majority of students (88%, in this example) are using social media with integrity, discretion, and wisdom. By defining what is normal and typical among the student body, it helps to induce the remainder to get “on board” through the power of positive peer pressure.

3. Student-led initiatives

Adults are doing a lot of good work, but it’s repeatedly evident that students are the most powerful catalysts for change on their campuses and in their peer groups. They are the real experts at what it means to be a kid these days, but often we don’t tap into their knowledge and experiences to help convey the right messages and set the right standards. The last thing we want is to waste time, effort, and resources on adult-led initiatives that students know would never gain any traction. Since teens are fully immersed in all things technological and social, it is crucial to enlist their assistance in promoting and celebrating digital citizenship, setting the tone and tying it into the school’s identity, and determining how to get the entire student body to help make kindness go viral.

4. Resilience

Generally speaking, resilience is the capacity to bounce back and successfully adapt in the face of adversity. Some interesting findings on this topic came out of one of our recent papers. Of those students who were cyberbullied, those with the highest levels of resilience were least likely to be phased by it in terms of their ability to learn and their feelings of safety at school. Those with the lowest resilience were more likely to say that it negatively affected their school experience.

In addition, students with high resilience who were cyberbullied were more likely to utilize prosocial responses–like reporting it to a school authority, to the site or app on which it occurred, changing their screen name, blocking the harasser, or logging out. They believed in themselves and their ability to do something about the problem. However, those with the lowest levels of resilience, when cyberbullied, did nothing. They suffered silently, because they didn’t know they had agency and autonomy to control their online experience.

Finally, among those students who were cyberbullied, those with higher levels of resilience were less likely to be bothered overall, and less likely to get sad, angry, frustrated, fearful, or embarrassed because of it. Why does this matter? In the field of criminology, research consistently demonstrates that youth who experience these negative emotions often haven’t developed positive coping mechanisms to reconcile them, and so they end up acting out either in self-harm or interpersonal harm and violence.

Diffusion of Benefits

The topics I have discussed today have similar implications not just for cyberbullying, but for general student well-being and school safety. Creating and maintaining a positive school climate can help reduce a host of problem behaviors because adults have better relationships with the students under their care. Setting appropriate social norms can convey that the clear standard among the student body is that everyone looks out for one another, no matter what. Student-led initiatives allow youth to play an enthusiastic and meaningful role in shaping the quality of their school environment. And as mentioned, resilience programming can help students discover their own ability to be overcomers and rise above the stressors that come their way – social, relational, or otherwise.

Conclusion

I believe the federal government can support these efforts by providing additional personnel and funding to schools to implement these recommendations with fidelity. Second, scholars need funding to do more evaluation research to determine how well these initiatives are working, and how they can be tweaked to be even more successful. Third, we need better ways to get these evolving best practices into the hands of those who need them. Fourth, we need mechanisms for accountability not just at the school level, but at the state and federal level. This will help ensure that adequate resources are provided so that our students can thrive, and our communities can flourish.

Thank you for your time.

Suggested citation: Hinduja, S. (2018). Federal Commission on School Safety. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/federal-commission-on-school-safety