When we speak to students in schools across the nation, we always focus on the positives of social media while also sharing case studies to underscore the reminder they frequently need to hear: “pause before you post.” While there are numerous examples of students missing out on college and university slots, scholarships, and employment opportunities based on their tweets, status updates, and other online posts, some consequences are much more severe. For instance, threats made by students – regardless of whether they are in jest – are truly serious offenses, and can lead to a juvenile or even adult criminal record.

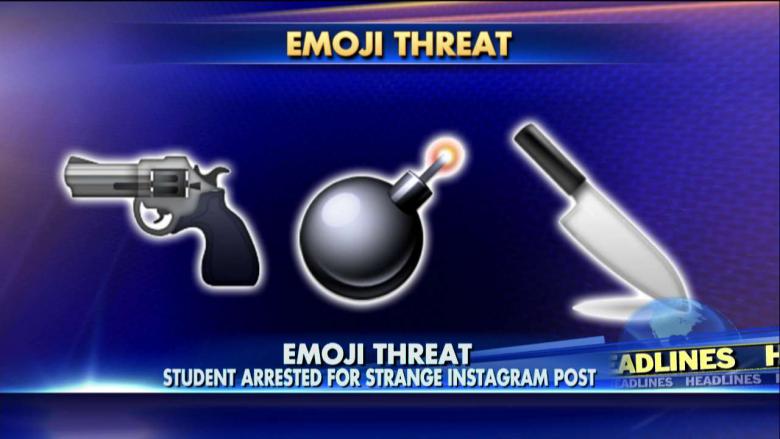

This got me thinking about the use of emoji in our Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter posts – as well as in our iMessages and texts. Emoji debuted way back in 1999 in Japan with a set of 176 symbols, but exploded in popularity in 2011 when Apple came out with the iPhone 5. These days, we are up to over 2,600 emoji in the Unicode standard, and at least a few of them can be used to convey a threat, depending on one’s interpretation. If you use a bomb emoji within the context of a message you send or post, how might that be interpreted by a school? By law enforcement? What about a knife or gun emoji?

Many of us may share various emoji in humorous ways, but it’s important to remind students to exercise incredible wisdom when including them within posts that may possibly be viewed as threatening. After doing a review of some cases (let me know if there are any others you’ve found that we haven’t), it is clear that some uses of specific emoji when communicating certain sentiments may be viewed as hostile, menacing, or foreboding – even if one can make an argument that they weren’t meant as such. It may not matter, because in these cases, the culpable middle or high school student faced punishments that not only involved suspensions or expulsions, but also probation and felony convictions. Here’s what we found:

JS v. Grand Island Public Schools, 899 N.W.2d 893, 297 Neb. 347 (2017)

On Sunday, April 3, 2016, a group of students from Barr Middle School were on a social media website. A post was made anonymously which read “Tomorrow gonna be hella fire [fire emoji] be there (School).” This post was then followed by another anonymous post: “Don’t show up to school tomorrow [gun emoji].” That night, Barr employees were notified by the Grand Island Police Department regarding these online posts. On April 4, 2016, extra security was present at the school while a search for potential treats was conducted by police and staff. While conducting interviews, the police and Barr staff were able to identify who had made the anonymous postings. J.S., during her interview, admitted to making the “hella fire” post. The post with the gun emoji was not made by J.S., and no evidence was uncovered that she had any connection with the second post. Barr’s principal sent J.S. home and suspended her for 15 days. The court affirmed the suspension, reasoning that J.S.’ posting could be interpreted as one of violence, and that it set into motion a series of events that caused a substantial disruption to the school environment. J.S. appealed, but that appeal was dismissed.

Shen v. ALBANY UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT, No. 3: 17-cv-02478-JD (lead case) (N.D. Cal. Nov. 29, 2017)

A student created an Instagram account in November 2016 and provided access to a group of Albany High School students. In March 2017, the AHS student body and school personnel discovered the account and identified that it almost exclusively included extensive and extreme racist and derogatory content, including many laughing emoji in posts and comments.

Examples of hateful content included:

a “Ku klux starter pack” featuring a noose, a burning torch, a black doll, and a white hood.

a screenshot of an African-American student from her own Instagram page, which she had captioned “i [sic] wanna go back to the old way,” juxtaposed with an image of a white man beating a black slave hung by his hands. The image posted is captioned “Do you really tho?”

Multiple comparisons of African-American women and students to gorillas.

The back of a female African-American AHS student’s head captioned “Fuck you.”

Ten different AHS students were depicted, and several photos were taken on school property. Over the course of a weekend, a few targeted students were shown content from the account. By Monday, a distraught and agitated group of students (including some of those featured in the account) had gathered in a hallway – some in tears and some yelling. After an investigation, sanctions were doled out. The school district the proceeded to expel the account’s creator (who had uploaded all of the images) and suspended the other students involved (who had liked or commented on the posts, or took photos that ended up on the account, but did not directly post images). Ten plaintiffs – the one student expelled and the other students who were suspended – then sued the Albany United School District for First Amendment violations.

The court upheld the school sanctions for six out of the ten students, stating that their actions caused a substantial disruption at Albany High School. The plaintiffs tried to minimize the level of disruption by arguing that the district overreacted, but the court held that the targeted students found out about the Instagram account on their own and had very strong reactions. In addition, the plaintiffs were found to have clearly interfered with “the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone” (a hallmark standard from the most famous case involving student expression and school discipline – Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969)).

In this 2017 case, the court succinctly justified their ruling by remarking that all students have the right to “be free from online posts that denigrate their race, ethnicity, or physical appearance, or threaten violence.” To be sure, the laughing emoji in the posts and comments were not the primary reason for the severe student disciplinary measures. However, it is arguable that they demonstrated a callousness, haughtiness, and arrogance that lent believability to the intent of the hate and of the threats.

IN RE LF, No. A142296 (Cal. Ct. App. June 3, 2015)

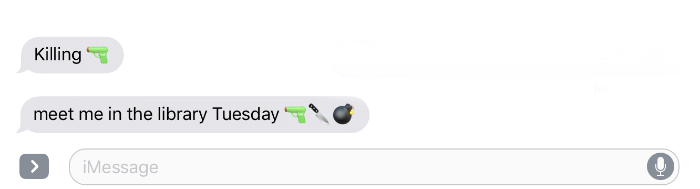

One evening in May 2014, a parent of two girls at Fairfield High School was told by one of them that she didn’t want to go to school the next day because someone had posted on Twitter that they were going to shoot it up. The parent then looked at the tweets on his daughter’s phone, and decided to call the police. A police officer arrived at that parent’s house, and he showed the officer the tweets.

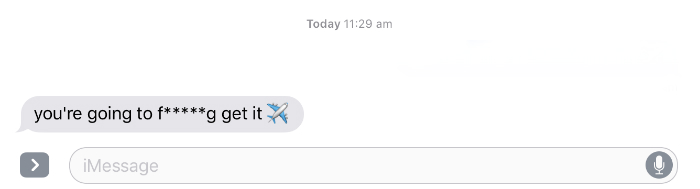

Among Minor’s tweets, made over the course of approximately three hours, were the following:

“If I get a gun it’s fact I’m spraying [five laughing emoji] everybody better duck or get wet”

“I’m dead ass [three laughing emoji] not scared to go to jail for shooting up FHS warning everybody duck”

“Nigga we ain’t fighting I’m bringing a gun [six laughing emoji]”

“Mfs don’t really kno me [two laughing emoji] I have touched a gun pointed one don’t […] Bitch I kno how to aim”

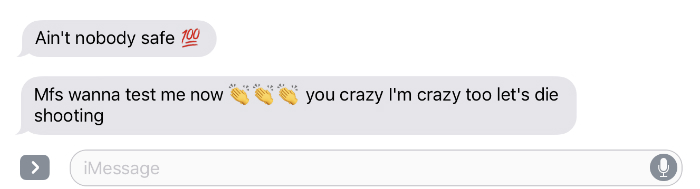

“Ain’t nobody safe [`100′ emoji]”

“I’m finnah come to FHS like black opps stabbing niggas! Who really with it?”

“@[username] idk when shit go down prolly the next day”

“And wtf lol tf you getting popped first fr try me [laughing emoji]”

“It’s funny cause nobody fighting no more sooooo!! I’m just shootin niggas for fun”

“Mfs wanna test me now [three clapping hands emoji] you crazy I’m crazy too let’s die shooting”

“I’m leaving school early and going to get my cousin gun now [three laughing emoji and two clapping hands emoji]”

“Y’all gonna make me go to jail before I step foot on campus [laughing emoji]”

“I really wanna a challenge shooting at running kids not fun [laughing emoji]”

The officer went to Minor’s home, placed her in handcuffs, and read her constitutional rights. Minor said that she did not mean the statements she had made on Twitter and that they were a joke. She was unable to explain why she made the statements. The district attorney filed a juvenile wardship petition alleging that the student had made felony criminal threats against FHS students and staff, and the court found that the tweets were a threat beyond all reasonable doubt. She was then placed on probation. Minor appealed on multiple ground, but the appellate court denied the motions and upheld the lower court’s finding that the threats were criminal.

It’s pretty clear – regardless of whether students are trying to be funny or convey anger and frustration or make some sort of line-in-the-sand statement with or without emoji included, they should tread carefully and make sure no one can possibly misconstrue what they are saying and intending. I hope you share these case studies (edited for language, of course!) with your middle and high schoolers so that they deeply understand the ramifications of these posts and messages. I know so many struggle with an invincibility complex and think that these sort of things would never happen to them – because they are smart and savvy and know exactly what they are doing. I want to believe that about them. But the reality is that the individuals in the cases above probably never thought they would get busted. But they did.

Suggested citation: Hinduja, S. (2018). Emoji as Threats in Student Messages and Social Media. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/emoji-as-threats-in-student-messages-and-social-media

Image sources:

https://ab.co/2HegKOi

https://bit.ly/1Rcu9DA