“There’s one way to love you but a thousand ways to kill you. I’m not going to rest until your body is a mess, soaked in blood and dying from all the little cuts. Hurry up and die, bitch, so I can bust this nut all over your corpse from atop your shallow grave.”

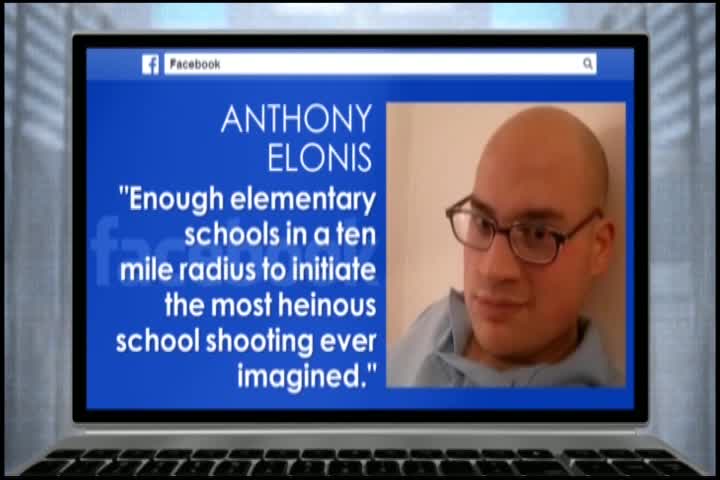

These comments were posted to Facebook by Anthony Douglas Elonis in 2010. They were directed toward his ex-wife. Do they constitute a threat? Is what he posted illegal? The Federal Bureau of Investigation was made aware of this and began to monitor Elonis’s online activities. A special agent paid him a visit. Elonis commented on this meeting in a subsequent Facebook post: “Little Agent Lady stood so close/ Took all the strength I had not to turn the bitch ghost/ Pull my knife, flick my wrist, and slit her throat.”

As a result of these and other comments, he was charged with five counts of violating 18 U. S. C. §875(c) which states: “Whoever transmits in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.” Elonis argued that his comments were merely a form of art therapy: His wife had recently left him and he was just struggling with sorting it all out. He intended no harm. They should not have been read literally or viewed as threatening. They were rap lyrics, no different from what superstar musicians regularly sing on stage. (It bears mentioning that his former wife had never known him to write rap lyrics at any time during the 7 years of their marriage.)

Upon hearing the case originally, the federal trial court judge instructed the jury that “Elonis could be found guilty if a reasonable person would foresee that his statement would be interpreted as a threat.” Given that standard, I think the jury rightfully returned a guilty verdict. Most reasonable people I know would view these comments as threatening. He was sentenced to forty-four months in prison. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals reviewed the case and agreed with the original finding, stating that a reasonable person would view the content as a threat.

Limits on Free Speech and Criminal Accountability

In the United States, the First Amendment to the Constitution grants us the freedom to say pretty much whatever we want. The key modifier here is “pretty much.” Despite what some free speech advocates might have you believe, there are some specific restrictions to what we can say. Most famously, for example, we can’t yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater (Schenck v. United States, 1919). Also included among the “list of things we can’t say” are what the law calls “true threats.” The Supreme Court has never precisely defined what constitutes a true threat, but the lower courts have provided some parameters, including that the threatening speech in question be directed at a particular person, a reasonable person would interpret the message as serious, and the speech is communicated by someone who has the ability to carry out such an act.

But when it comes to criminal law, there is also a question of intent. By default, in any criminal case, prosecutors must prove that a defendant intended to engage in the act that is proscribed – that they are “blameworthy in mind” (referred to as mens rea). This standard applies even if the specific statute doesn’t expressly include an intent requirement (see, Morisette v. United States, 1952). A number of very specific exceptions to this rule have also been carved out over the years (e.g., statutory rape or other so-called “strict liability” offenses). Absent an explicit exclusion, however, intent is always an element that must be proven. So, did Elonis intend his comments as threats?

Supreme Court Ruling

In the end, the Supreme Court sided with Elonis. They didn’t say he had the right to post these comments online. They didn’t argue that his remarks are protected speech. And they agreed that most reasonable people would be threatened by the comments. But they still overturned the conviction. Say what?

The Court focused on one very specific aspect of the case: the jury instructions. The majority ruled that the judge was incorrect to instruct the jury to utilize the reasonableness standard. Even though it wasn’t stated in the law (actually, perhaps precisely because it wasn’t stated in the law), the intent of the person conveying the speech matters. Even though most people would view the words as a threat, what really matters for this particular statute (18 U. S. C. §875[c]), is whether the person making the comments did so with the intent to threaten. And that apparently wasn’t established in this case.

The Supreme Court refused to tackle the more important questions of whether Elonis’s comments were in fact protected speech (or “art”) or whether his comments were reckless and that he should have known that they would have caused harm: “The Court declines to address whether a mental state of recklessness would also suffice. Given the disposition here, it is unnecessary to consider any First Amendment issues.”

What Now?

So where does this leave us? Unfortunately we aren’t any closer to understanding the point at which online speech crosses the line to become a crime. Am I now free to post comments of a threatening nature so long as I include the caveat that I do not intend them as a threat? What if I include “JK” or a smiley-faced emoji? What about Justin Carter, the Texas teen who spent months in jail for making what most agree was a sarcastic threat in an online video game?

The Elonis ruling is just too limited to cover any of these scenarios. As UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh remarked in a recent Washington Post commentary: “The statutory decision that the Court reached, while important for deciding how to instruct juries in federal threats case, is likely to practically affect the results in only a narrow range of cases.”

It should also be noted that just because criminal courts can fall short when dealing with some of these behaviors, it doesn’t mean that one can say whatever one wants without consequence. State laws could still apply (because the Supreme Court was only evaluating the federal statute). Moreover, online threats that don’t reach the level of a crime could be pursued in civil court, where the standards for conviction are much lower. So even though Elonis’s criminal court conviction was overturned, he could still be held accountable in civil court. Indeed, the Supreme Court acknowledged Elonis: “Elonis’s conviction was premised solely on how his posts would be viewed by a reasonable person, a standard feature of civil liability in tort law inconsistent with the conventional criminal conduct requirement of ‘awareness of some wrongdoing.’”

This is yet another example of why it is difficult to craft a criminal law to adequately address these kinds of problems (see also my analysis of Albany County’s Cyberbullying Ordinance). And especially when it comes to these behaviors perpetrated by adolescents, the emphasis should be on resolving them outside of the formal justice system. Hopefully then all involved can work to respond in an appropriate and reasonable way that stops the hurtful behaviors without becoming mired in courtroom technicalities.

Image courtesy of wkyt.com